It’s not often you see a room full of teenagers held in rapt attention while someone gives a history lesson, but sitting in the Dr. Eells Underground Railroad Home, Board Member Dave Oakley painted a compelling picture for the visiting students from the Quincy Teen REACH program. In 1842, Quincy had only been incorporated as a city for two years. Missouri was nearly the wild-western frontier of major settlements in the US. A strong tension had already gripped the nation and would eventually boil over into Civil War in the years that followed. Nowhere was this tension more palpable than in Quincy, a major river hub at the time, which sat at the border of the slave state of Missouri and the free state of Illinois. One hot summer night that August, an enslaved man from Monticello, Missouri known only by his first name, Charley, stepped onto the Missouri side of the Mississippi shoreline and began crossing to get to Illinois.

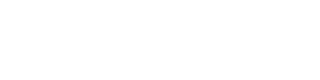

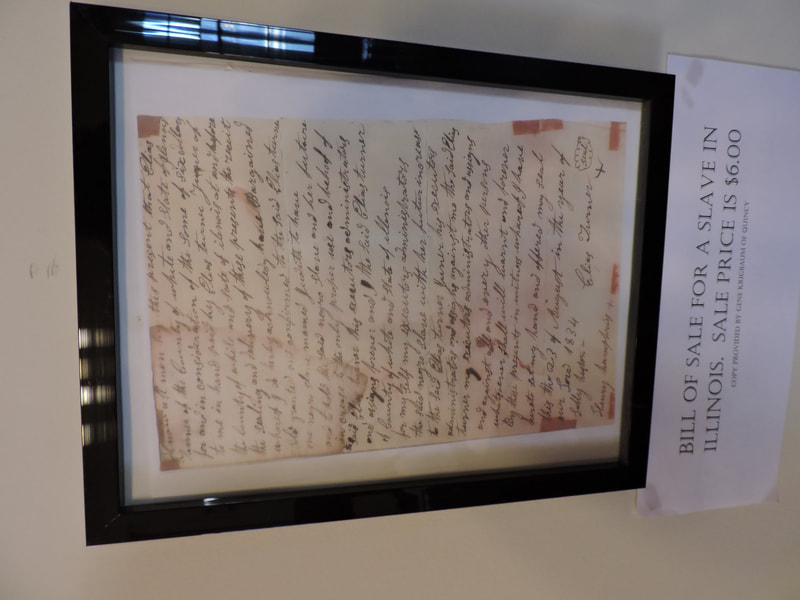

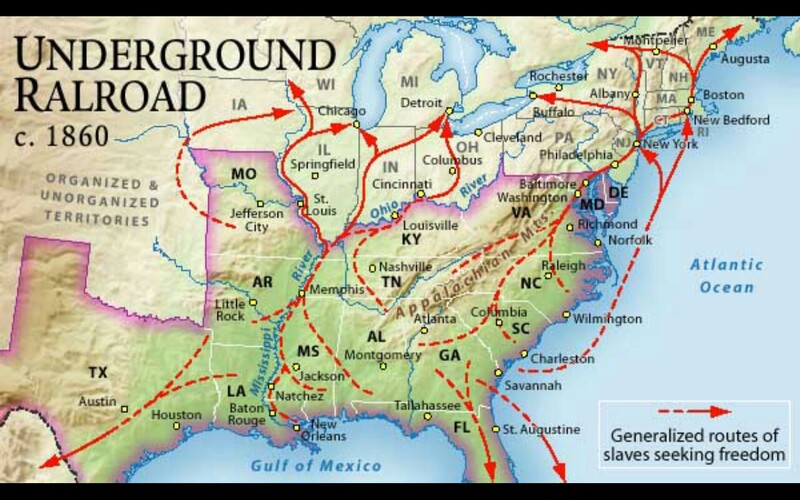

On the other side of the river, a physician named Richard Eells and his wife Jane were inside a stately, two-story brick Greek-revival style home on what is presently 4th and Jersey St. Dr. Eells had been educated at Yale University and then moved to Quincy from Connecticut. He had established a successful medical practice, adopted two children, and built on an addition to his home by 1842. He was a well-respected member of the community and was a trustee of the Congregational Church of Quincy. As Charley crossed the river that night, few would have suspected that his intended destination would be the home of this prominent physician. However, Charley would head for that doorstep with the hope that it would be the first stop on his way to freedom. “So he just swam across the whole river?” interjects a teen audience member named Aleirra. “Wasn’t that dangerous?” Indeed, it was dangerous, explained Oakley. In the 1840’s there were no dams so the river was not necessarily as wide or deep as it is now. In fact, if the water was low it was likely possible for someone to walk across much of the river until the channel and get mud between their toes! It’s not hard to see that Charley was already taking an enormous risk just setting off for Illinois with low or high waters. Of course, Charley wasn’t the only one taking a major risk that night. Each time Dr. Eells took in a runaway slave, gave them provisions or moved them on to the next location on the Underground Railroad, he was risking his life and livelihood for a stranger. Another student, Jacob, offered, “That’s crazy what the doctor did. He already had his life right and he could have just been making money and living life but he chose to help.” The doctor was taking a major risk by helping the runaways, but helping free individuals from slavery was the original motivation for Richard and his wife moving to Quincy. While he was in school out East, he became interested in the abolitionist movement, and as he learned more, he knew he had to take action to help. It’s important to remember that merely making the swim to Illinois was not enough to grant Charley or other runaways their freedom. Though Illinois was a state without slavery, the law of the time demanded that any slaves in Illinois must be returned to slaveholders in Missouri (or other states) or the person found harboring them could face prosecution and fines. Charley’s long-term goal was to travel the Underground Railroad all the way to Canada, where he would finally be able to live a free life. At this point, one of the younger students listening to the lecture started looking all around the room at the floors before he finally asked, “So where are the tunnels?” The title “Underground Railroad” can be a bit of a misnomer, and many visitors to the Dr. Eells house expect a tunnel system to be inside the house. Instead, the word “Underground” is in reference to the secrecy that surrounded the safe houses and transportation methods. Railroad terms like “station” were used to describe the safe places that the travelers could stop, rest, and replenish their supplies on their way north to Canada. Known nearby stations beyond Quincy included stops in Mendon, Meredosia and Pittsfield. Many slaves of the time were unable to read, so the “railroad” was constantly innovating different types of communication that would signify to escapees which houses were safe to enter along their route. Dr. Eells and his wife are credited with helping several hundred slaves escape to continue their journey on the railroad, but the night Charley crossed the river, they were not so lucky. Eells provided Charley a new set of clothes and some provisions, then tried to take him by carriage to a second stop on the railroad called the Mission Institute, but slave catchers working for Charley’s owner intercepted them both. Eells yelled at Charley to run, but he was soon captured by the posse of men. Eells escaped the group and arrived back to his home, but the sheriff wasn’t far behind. The sheriff used the fact that Charley’s wet clothes were in the carriage and Eells’ horse was sweaty and lathered from running as evidence that Eells had been the one trying to help Charley. Eells was later brought to trial and found guilty by Judge Stephen A. Douglas, who, several years later, would debate Abraham Lincoln just a block from the Eells home, in what is now Washington Park. Sadly, Charley was returned to Monticello and Dr. Eells was fined $400 - about $12,000 in today’s money. The Eells prosecution and subsequent appeals all the way to the US Supreme Court were followed closely by Quincy’s Whig newspaper, and because of the notoriety of the case, Eells became president of the Illinois Anti-Slavery Party in 1843. He also became a candidate for the Liberty Party for the presidential election of 1844 and for the gubernatorial election in 1846. The case, however, drained Eells both emotionally and financially, and he died while traveling back East on the Ohio River in 1846, having never been cleared of the charges. Fast forwarding over 150 years to 2015, former Quincy Mayor Chuck Scholz and former President of the Dr. Eells Home John Cornell proposed the idea of gaining a pardon for Eells. The local team, along with Lt. Governor Sheila Simon and Governor Pat Quinn worked together to facilitate a wide-ranging clemency action which formally pardoned Dr. Eells and two other 19th-Century abolitionists from Jacksonville who had been convicted of assisting escaped slaves. “It’s important for all of us to remember heroes who spoke up and acted at great risk to themselves for what was right, even when they knew it was not what the law would support,” said Lt. Gov. Sheila Simon* in the Chicago Tribune. “I think we need more reminders of that.” Today the Dr. Eells Underground Railroad Home is preserved by a small group of dedicated volunteers. The home is typically open for tours on Saturdays from 1-4 pm from April - November and groups can schedule tours by appointment by calling 217-223-1800. Donations can be made to: Friends of the Dr. Richard Eells Home, PO Box 628, Quincy, IL 62306.

1 Comment

Laurie James

11/5/2022 07:17:51 am

I find the tour perplexing that in a white city like Quincy, the children were all black.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed